I’m fascinated by people that don’t know anything. Ok, perhaps not anything, but simple things. Like, “How do you get there?” I don’t know about you, but there’s this nifty new invention they call a map. “Where do I get one?”

I taught college-aged kids for a short time, and I was fascinated by one particular fact – none of them knew how to find out any information on their own. This boggled me, as they all had phones in their pockets and computers on their desks, two items they grew up with all around them. And yet, they didn’t know that you could use them for anything else than Facebook or Snapchat.

I’m from the generation in which computers became prevalent during my young adulthood. I think that puts me in a unique position that people my age and no others have; we know how to look stuff up.

When I was young, and you didn’t know how to change a tire, you asked your dad. Or you looked in one of those Time/Life books. Or you went to the library (which was tough, since you had a flat). But you reached out to others to learn things. Maybe you called the theater to learn the movie times (“Welcome to MovieFone!“) or you opened the paper. You asked a friend how they drew that doodle. You raised your hand in class when you didn’t understand a word. But you asked, you looked for the answers, and sometimes those answers took you a while to find. But you found them.

Today, we have access to information on a colossal scale. And it is information shared by not only professional sources, but amateur as well. People know stuff, and they want to share it. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve watched a shaky phone video of a guy explaining how to get some part installed on a vehicle – on not just any vehicle, but my specific year, make and model. In my youth, that was never even dreamable.

But there’s a drawback to this. Several, in fact. For one, some people just don’t know how to find anything. I’ve been asked innumerable times, “How do you find info on <subject>?” It never occurs to many that you can just Google <subject> and find a treasure-trove of information. Secondarily, information itself is at risk. Why learn anything if you can just look it up at a moment’s notice? Why read? Why watch? Why experience things? But the biggest drawback, I think, is that the wealth of information, news and data, complicates life for people, even as it is supposed to simplify and educate them.

I recently had a conversation with a man in his seventies, and he was lamenting the (in his mind) fact that life was much simpler when he was a kid. Things that happen today weren’t happening. We didn’t see all this news about people protesting, and refugees, and terror and whatnot. It was a simpler time.

Except that it wasn’t. But the perception of simplicity was there. Why? Because today, with this wealth of information, you can know what a single person in Cairo is thinking right now, or what is happening in Bangladesh, or how many fisherman are out of work in Alaska. All that stuff was happening “back then”, but you didn’t know about it, because your information resource was a local daily paper 30 pages thick.

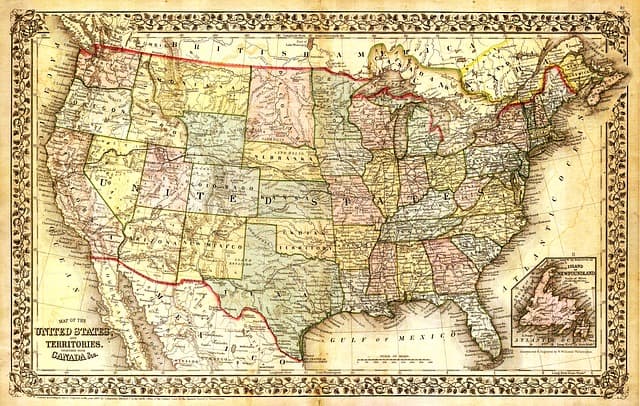

So how could you not know anything today? Or be bored? Bored!? It seems to me that, with the preponderance of information and entertainment, there is so much “on” that, at times, it seems like there’s nothing of interest. The bar has been raised. Instead of four channels, we have thousands. Instead of a VHS tape of Annie, we have hundreds of movies streaming RIGHT NOW. Instead of a map, we have fifteen different apps that all tell me the same way to get to the same place.

Google maps, person in the first example.

But unless we embrace the information, and become involved with it, we’ll feel the same way. USE the info, don’t let it use you. Don’t let it suck you in and pull you away from learning a wealth of fascinating info about your street, your town, your world. It’s there, you just have to look for it.

Now excuse me, I must get back to cat videos.